Super Constellation Starliner Aircraft

Case Study

Super Constellation Starliner

Auburn-Lewiston Airport, Auburn, Maine

– Case Description

The once-regal Super Constellation Starliner, the legendary luxury aircraft designed by Howard Hughes and built by Lockheed Martin, appears like an oversized model in a cavernous hangar at the Auburn-Lewiston airport in Maine. A team of experts, working like surgeons around a (radiantly heated) operating table, are bringing it back to life. But as the operation is occurring over an extended period of time, a way to heat the hangar to keep the restorers comfortable was needed.

Summary

THE SEED OF THE RESTORATION IDEA

The idea of restoring a Constellation entered the radar screen at Lufthansa Airlines around 2003. Ultimately, the German firm bought three of the last remaining airplanes, none of which were in good condition. The purpose is to restore one, maybe two, of the aircraft back into flying condition by cannibalizing parts from all three of them. A team of restoration experts, many of them flown from Germany to Maine, have been at work on the one plane. Unlike the rest of the plane, which will be restored to 1950s vintage, the cockpit will be fitted with modern gadgetry to allow the plane to be certified airworthy. Lufthansa experts say the avionics of the project alone will require 18,000 man-hours. The guts of the plane and the 30,000 pieces of its skeleton have all been tagged and cataloged.

A TALE OF TWO PLANS

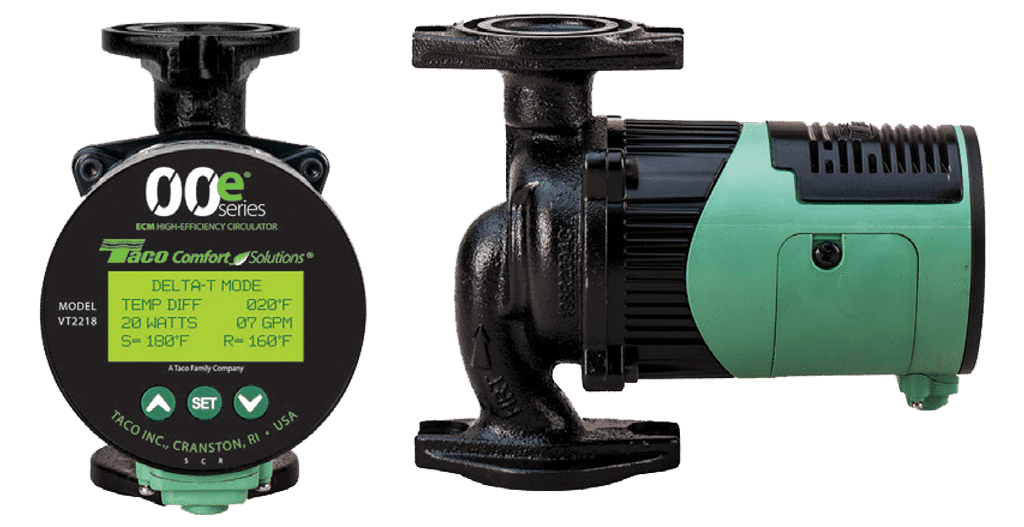

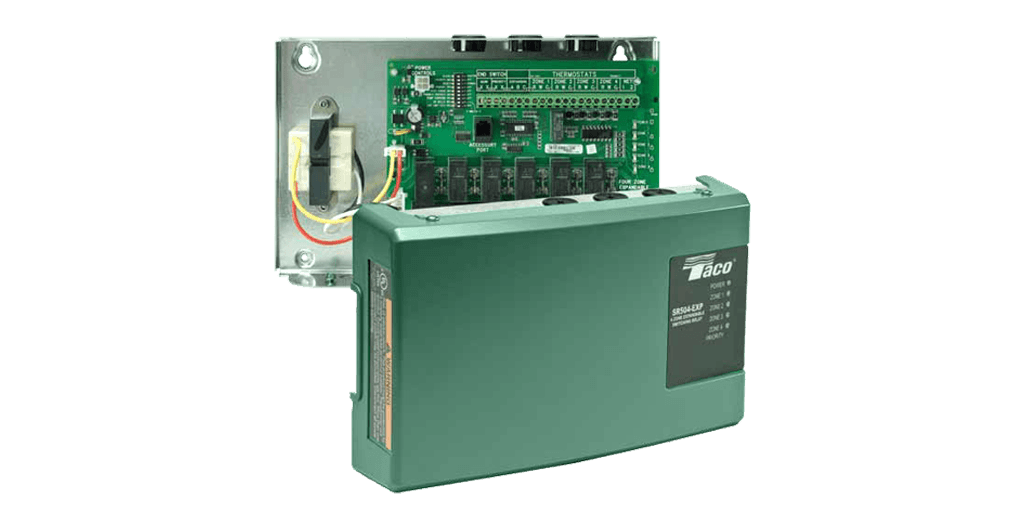

When the experts at manufacturer’s rep firm, Emerson Swan, and their wholesaler partner F.W. Webb, got wind of the project, they partnered with engineer Jeff Landwehr from Old Town, Maine-based Carpenter Associates to design a system that would hydronically heat the airplane hangar’s high-mass concrete floor. “An airplane hangar is perhaps the ultimate use of radiant heat,” said Jim Simas, regional sales manager for Emerson Swan. “With giant, open areas, it’s no place for forcedair heat; in the winter, Btus would be flushed out fast with the opening of the big bay door. And even with the place buttoned-up, the guys working on the plane all day would have no floor-level heat.” The construction project began in 2008. According Simas, the big hangar was divided into two main radiant zones and a much smaller one to serve a long, narrow snow-melt zone that extends 6 feet beyond the huge sliding doors of the building’s airplane-sized opening. With the mechanical room placed in one corner of the building, it made sense to run a 1-1/2- inch extended injection bridge to the manifold on the farthest side (with about 250-foot supply and return feeds), and a 50-foot, 2-inch PEX line set to feed the nearest manifold. According to the chosen hydronic systems installer, Al Hill, Al Hill Plumbing, the company used oxygen-barrier RadiantPEX tubing and stainless steel radiant manifolds manufactured by Watts Radiant. Hill, a British hydronics pro who made his way to Maine 27 years ago, was just the right guy for the job. Each of the two large manifolds for the main area supplies warmth to 24 400-foot, ⅝ -inch PEX loops spaced on 18-inch centers in the main floor of the hangar. Spacing is snugged closer at 9-inch centers near the exterior walls and the snowmelt apron. Two gas-fired boilers feed 180˚F water out to the manifolds. Return fluid temperatures typically reenter the primary/secondary piping at about 80˚F. “With return temperatures like that, each gallon delivers between about 40-50K Btu,” said Simas. “One design that was initially considered delivered a 20˚F Delta T,” explained Simas. “But cost was the major obstacle to building the system to accomplish it. Our alternate plan — which brought the price of installation down substantially — won approval and worked marvelously through its first winter, even when ambient temps dipped well below zero.” According to Simas, the initial design called for a greater number of pumps and massive, 2½-inch copper lines suspended overhead to feed remote manifolds with a flow of 37 ½ gallons a minute each. That, for just onehalf of the building. “The pumps for the initial plan needed to be large enough to move much larger fluid volumes up, and through 1,000 or more feet of large supply and return piping … plus all of the radiant heat tubing,” he said. Ultimately, the cost of installation labor; hangers; lift rental; larger mechanical components, including the high horsepower, three-piece pumps; and giant copper “runway” (at $18 per foot) pushed the building owner’s decision toward Hill’s approach. That was the genesis of the 100˚ Delta T solution. “The plan we settled on saved a huge amount of money on the cost of the system and in energy consumption as well,” said Hill. “The ‘extended injection bridge’ concept called for the mixing of fluid temperatures at the manifolds and outside the mechanical room.” Three small, variable-speed Taco pumps now play a critical role in running the system, transferring a huge amount of energy to each zone. “In essence, each of the variable Delta T pumps acts like a mixing valve, blending 180˚F water straight out of the boilers with cooler return water, out to the zones at about 120˚,” added Hill. The Taco variable Delta T pump is the driver for the 180˚ water and also performs a key role in protecting the boilers. The primary-secondary piping protects the boiler with sensors that stand sentry at the supply and return ports. Too much cold return water shuts off the injection pump, allowing the boilers time to bring internal water volume up to temperature. As soon as it’s available, higher-temperature fluids are then put to use to mix and blend outgoing temperatures for the radiant floor system. Simas admits that this approach requires more time to bring fluid temperatures into operating temperature range, but ensures that the boilers aren’t thermally shocked. “We always use Taco equipment whenever we can,” continued Hill. “On this job, half a dozen pumps drive the entire system. We also used Taco hydronic relays, flow checks, and an expansion tank.” “Radiant is the only heat that allows such flexibility because the design temps are low and we take advantage of the larger Deltas to mix water,” added Simas. “When combined with simple injection-style controls, a system like this delivers modulated water temperatures to the radiant manifolds to prevent overheating. At the same time, it protects the boilers from thermal shock and fluegas condensation. It’s a plan that worked especially well for Lufthansa and the Connie’s project.”

Al Hill Plumbing techs lay tubing for radiant heat in an airplane hangar.

Final Result

IN ITS WAKE

The project brought one of the world’s largest airlines into a small community in Maine where it has had a substantial economic impact through contracts with local companies, jobs for local aircraft technicians and mechanics, and leaves a 27,000- square-foot, radiantly heated hangar for future use. When it’s complete, the Connie will be flown to Germany leaving a massive hangar that the airport can market for aircraft maintenance or refurbishing. Airport managers in Auburn say the hangar is a state-of-theart facility and, with the capacity to hold a Boeing 737, is the largest hangar in central Maine. With a real sense of excitement, they rewrote the airport’s master plan in 2005, calling for an expansion of the runway by 2013 to attract passenger service. Who could’ve guessed that an old plane, brought back from the dead, could make such a big impact internationally, and locally, too. In its wake will remain a fine facility to serve the community of Auburn. And whoever has the good fortune of working there, the miracle of modern hydronics will keep them comfy all winter long.

Jim Simas, of Emerson Swan, checks the system’s performance.